Catch you later(?) Understanding the impact of catch and release angling for elasmobranchs

In recent years there has been a steady push towards catch-and-release fishing within the recreational angling community, in many cases driven by a voluntary shift towards such methods by anglers. This is particularly apparent within the Irish shark, skate and ray angling community, where the vast majority of fish caught are released. However, it should be considered that, even with this widespread application of catch-and-release angling, a proportion of fish are still expected to die following release. These deaths are usually related to either direct injuries from fishing, or to the stress and energetic cost of capture and handling. Critically, while the impacts of catch-and-release angling are well documented for many bony fish, such as salmonids and members of the cod family, these have only more recently come into focus for elasmobranchs. This means it is difficult to determine what proportion of fish might be expected to die during capture, or post-release. While such impacts might seem trivial in the face of commercial fisheries operating on an industrial scale, they are nonetheless important to consider in the context of some of our rarest and most threatened species.

Commercial fisheries are generally considered to be the main global threat to elasmobranch populations, but there is now a growing appreciation of the potential impacts of recreational angling for these species. For some shark species, total catches by recreational anglers may even exceed commercial ones. This is most apparent within the United States, with more than 66 million sharks caught by recreational anglers between 2005 and 2015 along the U.S. Atlantic coast alone, including 1.2 million individuals of prohibited species, which cannot legally be landed. Globally, elasmobranchs (that’s sharks, skates and rays, among others) are estimated to represent approximately 5 - 6% of marine recreational angling catches. While there is limited information on the exact numbers of these animals caught by anglers around Ireland, it is likely that this number is in the thousands - if not tens of thousands - per year, and so the potential implications of angling should not be discounted

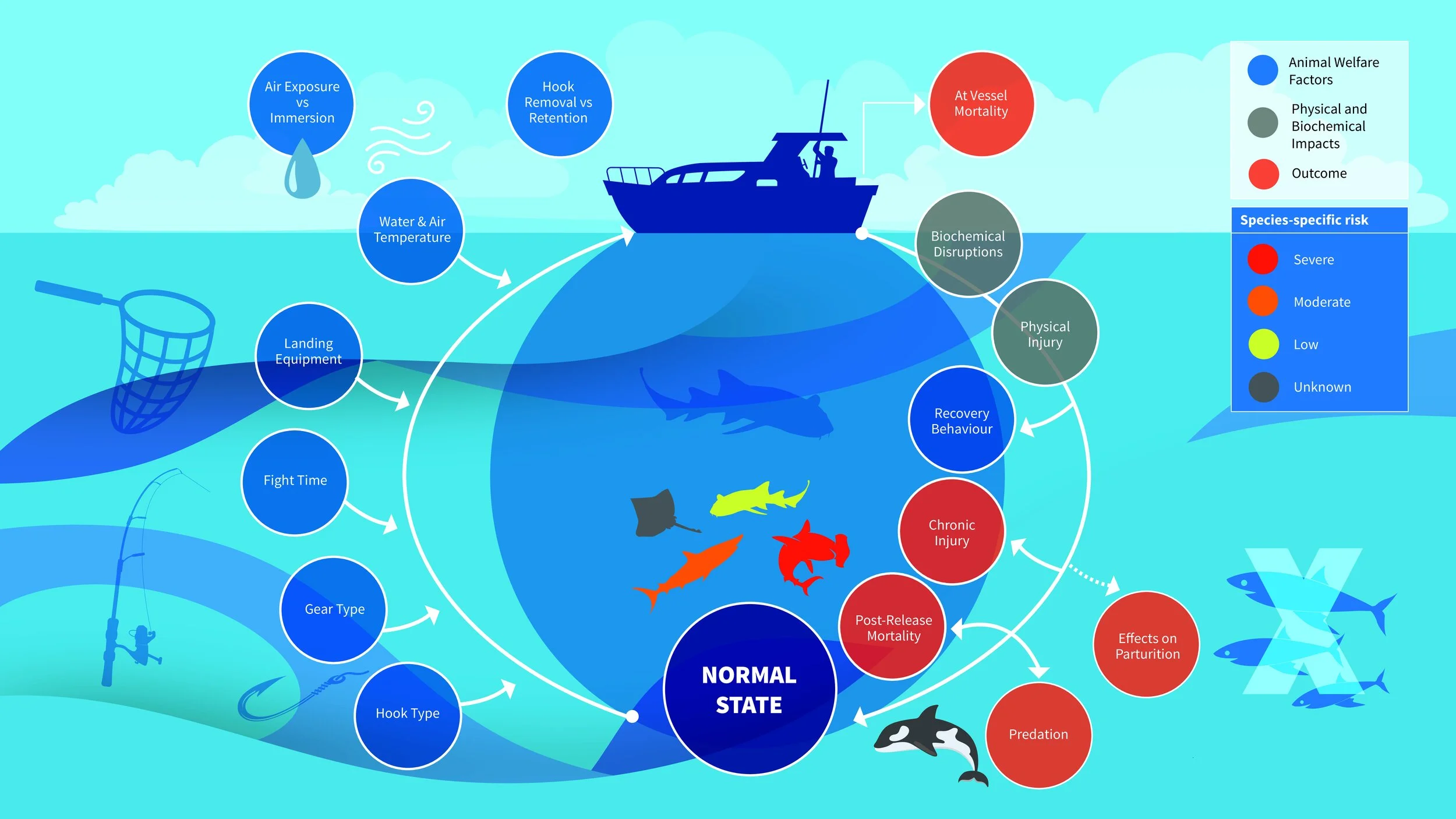

Therefore, in a recent review paper by the author and Irish collaborators, we attempted to summarize all current information on specific welfare factors associated with recreational angling, alongside associated mortality rates.

The science

We categorized the major angling-related effects into two groups: injury-induced effects; and biochemical disruption-induced effects. The former is mostly self explanatory, all angling involves some form of injury to the animal due to the use of hooks. These may be greater (e.g. fish hooked in the outside of the mouth) or lesser (gut- or gill-hooked fish) and can often be reduced by use of specialist fishing gear (e.g. barbless and/or circle hooks). The latter relates to the physical stress and energy expenditure associated with the capture and handling process, such as build-up of lactic acid in the muscles and blood, use of stored energy reserves, and release of stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol.

We then searched the scientific literature for all studies on these effects, and produced a summary of each group outlining the main lethal and sub-lethal outcomes. These outcomes include the most obvious post-release mortality, but also extended behavioural recovery periods in some species (which may in-turn confer increased predation risks). Severe and chronic health impacts from retained fishing hooks were also apparent in several species, including blue sharks. Lastly, we found evidence for numerous species which give birth to live young, where capture by anglers caused premature parturition (birth of offspring), in most cases this resulted in the death of the offspring.

Mortality rates associated with recreational angling vary greatly by species, with the most seriously affected including some species found in Ireland, such as thresher sharks. In the case of these large and distinctive sharks, animals are extremely prone to being foul-hooked in the extended upper portion of their tail fins, with the sharks then brought to the boat backwards, limiting water flow over their gills, and resulting in mortality rates of 26%. However, use of circle hooks appears to reduce the likelihood of such tail-hooking to almost zero, acting as a clear endorsement for their use. Other large Irish shark species, such as porbeagles and blue sharks, appear to be more robust to capture (although far from immune from negative effects), with the caveat that non-removal of fishing hooks can have severe and sometime fatal consequences for these animals.

An important - and somewhat unfortunate - finding of our study was that very little attention has been paid towards the majority of Irish elasmobranch species, with this most apparent for our skates and rays. This means it is currently impossible to give an accurate assessment of the impact angling may have on many of our most popular target species. However, we can make some broad inferences based on other species. In general, the most important risk factors to consider are animal body size, with larger animals at greater risk of post-release due to prolonged fight times, causing physical exhaustion; the method of gill ventilation, where species which must swim continuously to flow water over their gills are placed at a much higher risk (this includes most shark species); and feeding mode, where some species are much more prone to gut- or gill-hooking.

Takeaway points for anglers

The above points highlight the importance of appropriate equipment and handling practices for the species you are targeting, from the hooks used (e.g. circle hooks vs. j-hooks; offset vs. non-offset point hooks; barbless vs. non-barbless), to the line strength and overall gear class relative to the size of fish targeted, to the methods used to handle the animals (e.g. whether animals are kept in the water, whether hooks are removed, the use of gaffs vs. tail ropes or landing nets etc.). Across all studies these represented by far the most important factors in determining the survival rate of the animals captured. Most of these factors will likely seem obvious to dedicated anglers, however their impact on survival rates cannot be overstated.

Our research also highlighted a reluctance by many anglers to adopt certain equipment and methods which might improve the survival of the fish they catch, the most prominent example being that of circle hooks. The main reason for this among anglers appears to be the perception that circle hooks reduce catch rates, either through fewer hookups, or more fish lost during the fight; or that the change in fishing tactics to account for the use of circle hooks represents a challenge. Interestingly, a 2016 study by researchers at the USA’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) found that circle-hooks actually had higher hooking and capture rates for 10 shark species within the Maryland recreational sea fishing community, including blue sharks and several close relatives to native Irish species. Additionally, data from commercial longline fisheries for numerous species have shown that adopting circle hooks results in no discernable difference in catch rates. Therefore we would encourage all anglers to adopt their usage wherever practical, as this has clear benefits for both the fish and angler, in terms of hook location and ease of unhooking. One caveat to this is that we currently have little data on how circle hooks perform when targeting skate and ray species, with this being a key area for future study. An important point to consider when deciding which hooks to use is that the benefits of circle hooks can be enhanced by going barbless (further aiding ease of unhooking and likelihood of successful hook removal) and diminished by using offset-point hooks, with the latter increasing the rates of deep-hooking in most species studied.

Guidelines for best-practice

An in-depth guide to best-practice will be published on this site in due course, however the main takeaway points can be summarised below:

Use appropriately rated gear (e.g. when targeting larger sharks, such as threshers or porbeagles, use an 80 class lever-drag multiplier reel, big-game rod, minimum 80lb mono or 100lb braid mainline, 200lb+ rubbing leader to withstand these animals’ incredibly abrasive skin, and appropriate wire biting trace - we would suggest 450lb as a minimum). This will greatly reduce fight time, thereby improving survival odds post-release, and increase your chances of landing a PB without suffering a bite-off

Keep your catch in the water wherever possible. This is stating the obvious but always worth repeating. Most specimen fish committees (including our own ISFC) will now accept length measurements (or length + wingspan for skates) for most elasmobranch species, and length to weight conversions are readily available for many species, so - if you can - keep your catch in the water, take a quick measurement, a photo or two, and release.

Use non-offset circle hooks (ideally barbless) wherever possible. These will greatly aid in hook removal, reducing handling time, and minimise injuries to your target species. If you can, try to use hooks which corrode over time (i.e. non-stainless), these will minimise long-term impacts on the rare occasion they cannot be safely removed (make sure to store them in a waterproof sealed packet or container though, or you might just be disappointed when you next unearth you gear in a month or two’s time)

In line with the above, bring appropriate equipment to remove hooks. If you are targeting large sharks or skate this might mean having heavy-duty long handle pliers, a push/pull T-bar and bolt cutters on board. Being properly equipped will maximise your chances of safely removing the hook from anything you might catch.

Avoid use of injurious equipment, such as gaffs, wherever possible. Again, we’re stating the obvious here but gaffs cause injuries to the fish you catch. We understand they can often serve a practical function, particularly when landing big skate from a boat, but in most (if not all) cases they are only needed if the fish are brought onboard.

Call for angler information

As mentioned above, there is currently a lack of information on many skate and ray species. We are currently particularly interested in the effectiveness of circle hooks when fishing for these species. If you are interested in taking part in a study to determine the impact of circle hooks on catch rates and rates of deep-hooking please do get in touch.

Additionally, if you are aware of any occasion where you know or suspect a shark or ray has given birth during the capture and handling process we would be extremely grateful to hear from you. To be clear, we do not intend to blame or scapegoat anglers, however it is important to understand where, when and why these events occur (and for which species) to mitigate their potential impact.

Where to find more information

If you want to read more about this work, you can access the original research article here

Flow diagram representing the major animal welfare factors (inputs shown on the left); resultant physical and biochemical impacts (shown in grey); and outcomes associated with recreational catch-and-release angling for elasmobranchs. Species-specific risk categories are outlined for a range of different elasmobranch species found globally, including a nurse shark (low); a typical lamnid shark (e.g. porbeagle; moderate); a great hammerhead (severe); and for a ‘typical’ skate or ray (unknown)